Why We Need Extreme Examples To Live Up To

An offensive interpretation of Stoic philosophy with a Medal of Honor winner

I had the pleasure of being hosted by Kit Perez | Grey Cell Systems on her podcast. You can listen to the podcast here which goes live at 7:11 AM on February 3rd. We covered meaning, suffering, transhumanism, LLMs, and a host of other light topics. She is one of the best interviewers I’ve ever spoken with.

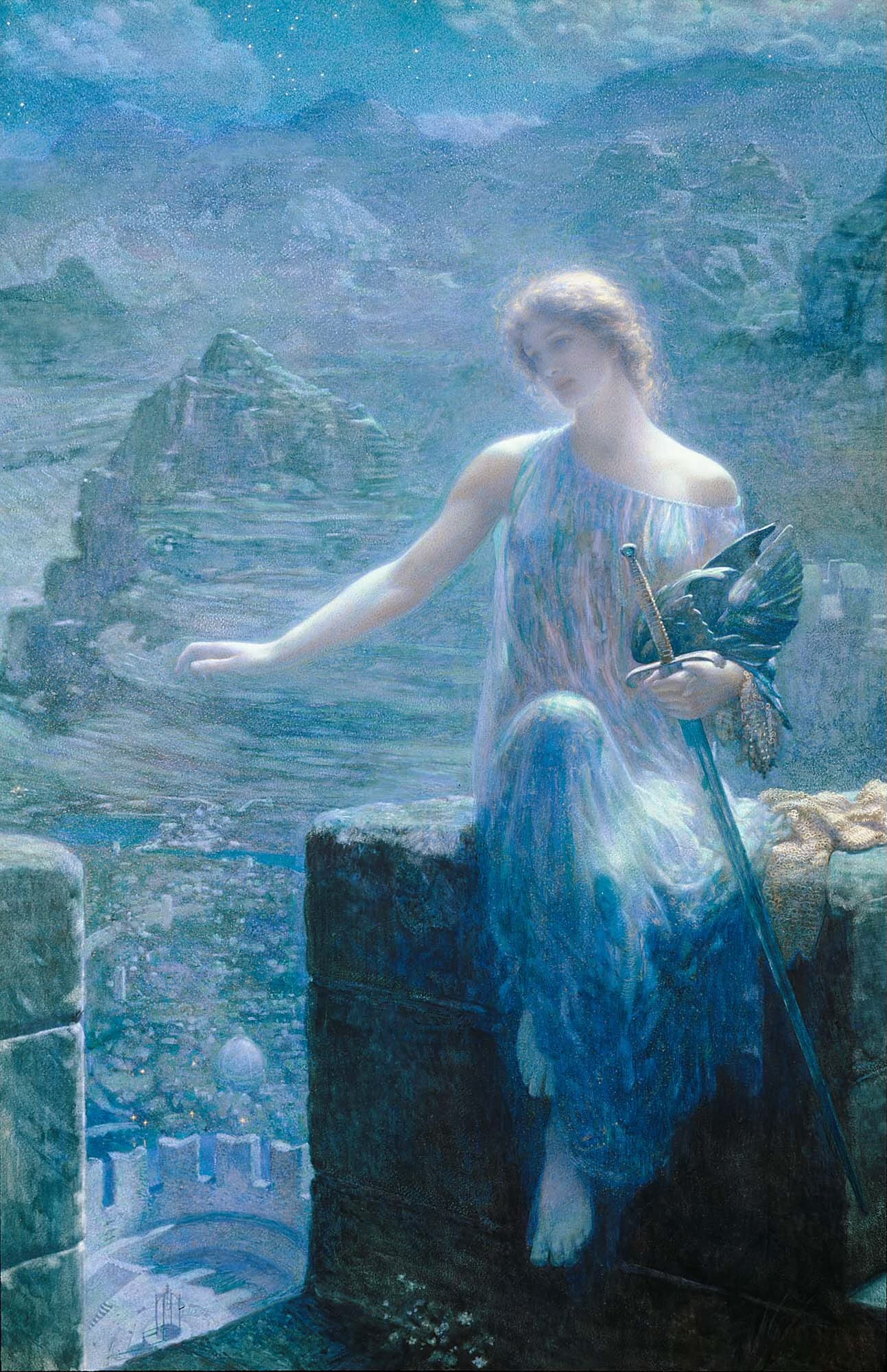

For today’s essay, the painting above is more fitting than usual. A belief in the valkyries was a belief in an extreme view of existence. Not in the present sense of “extreme” which has been corrupted by political connotations, but extreme in the sense of being unapologetically and immensely alive. This piece explores the idea of extreme examples to attain this state.

The usefulness of scouting the extremes—I love Epictetus. I admire his passion. I admire the masculine undertones of his philosophy and the elegance with which he puts it to words. I admire his unerring focus on the goodness within each of us and his equal contempt in how often we fail to live up to this goodness.

I also admire how he uses extreme examples to make his points. My hunch is he uses such extremes so that if his students take in merely two percent of his teaching, they will be better humans. I do the same in almost all of my writing, for these examples have a way of making our day to day ordeals not only easier in comparison, but explosive opportunities for growth. Extreme examples also give us something to aspire to, something concrete. Something real.

The invincible as an ideal—One of the Old Man’s quotes is particularly striking: “Who, then, is the invincible man? He whom nothing that is outside the sphere of his moral purpose can dismay.”

Epictetus was offering a solution to a problem he saw in the souls of those around him: thinking oneself ready for hardship—in fact, invincible—when one has not the slightest idea what actual hardship is. As in his time, so in ours. Where Epictetus spoke of beheadings, slavery, and drowning at sea, we can speak of infrastructure, supply chains, and geopolitical disaster. So when the power grid is sabotaged, what happens to these invincible individuals? Or when they lose our jobs, what then? Or when their grocery shelves are empty? Or when water no longer flows in their pipes? Or when enemy landing craft drop their doors on the coasts of their countries?

The problem is then compounded: without knowledge of how ungentle fate can be, they are left utterly unprepared for it. And then it is tripled: when they are unprepared, they are liabilities as opposed to assets. Not only to themselves, but to everyone else.

But the problem at present is even worse. There are many who read Epictetus and take refuge in the passive meaning of his philosophy. They do not see, or choose not to see, a more offensive interpretation. This means the problems Epictetus was trying to solve may never actually be solved, much less diagnosed. Epictetus himself has been made useless, detached from the cosmic whole and a mere prop for self-delusion.

The passive interpretation of the Invincible Man is that we should not be dismayed when terrible things happen. But what is the point in training to be undismayed if we do not understand how bad things can be? And if by some miracle we are truly undismayed, is it enough to remain calm when we have bills and no income? When the lights go out for good? When the war for water begins? Or is it to remain calm, and then act masterfully under duress for the good of others?

What would Epictetus say?

An offensive interpretation—My point is the philosophy of Epictetus can be as offensive as it is defensive, as savage as it is intellectual. I do not think Epictetus would have been tyrannical about his philosophy being personalized, given his hatred of tyrants. An offensive interpretation of Epictetus demands agency, sweat, risk, cold, fiercely independent thought, and a savage pleasure in learning what we are inside through incremental difficulties. It is to accept the world of safety, stability, comfort, and peace is a sliver of calm in the lull between the storms that make up the entirety of our species history—and future.

But this offensive interpretation is ignored. Probably for no other reason than that it is uncomfortable. It would not let us sit contentedly in a chair or a classroom patting ourselves on the head as if we have “done the work,” or convince ourselves we are fully awake when in truth we have never woken up.

The invincible are not merely unmoved by externals. They have so thoroughly mastered what is up to them in advance—when no one was watching—that they act with superhuman clarity when reality reasserts itself. They are masters of self-flagellation, and judge themselves far more ruthlessly than they would ever judge anyone else. They do not train for academic problems, but primal problems. And they do this for the good of the whole.

Extreme examples exist—There are many concrete examples of this version of the invincible man.

Here is one about a Medal of Honor winner. He was a member of a Studies and Observations (SOG) recon team in the Vietnam War, men who rank among the finest warriors ever to walk the face of the earth.1

These men were extreme, and exceptional.

John Kedenburg was a 23 year-old One-Zero, or leader of a SOG recon team in the Vietnam War. He and his 9-man team made of both Americans and Montagnard (or Yard) indigenous partner forces, got into a firefight during a mission.

A 9-man recon team stood against a 500-man NVA battalion.

The battalion pinned them down, only for the SOG team to shoot their way out with the 500 on their tail. Every time the team paused, the NVA hammered them with AK-47s, rockets, and grenades. During a hasty evasion, one of their Yards disappeared into the forest. The SOG team had to leave him behind. Kedenburg stayed behind as a one man rear guard to buy his team time again and again. At last, Kedenburg radioed for a string extraction through a hole in the jungle canopy. A string extraction is a long rope hanging from the bottom of a helicopter on which up to four men can clip themselves. The men then dangle beneath the helicopter thousands of feet above the jungle, their lives dependent on a thin metal carabiner.

One Huey hovered above the jungle canopy. Four of Kedenburg’s men clipped in and were flown out. Then the second Huey came in. Kedenburg and his three remaining men clipped in just as the NVA were breaking through the ring of fire reigning down on them from helicopter gunships circling overhead. At this exact moment the missing Yard showed up. Kedenburg could have given a thumbs up to the helicopter crew chief and ascended to safety out of the sweltering jungle and snapping bullets. He could have said it was too late, or that it was just a Yard, or that he did not see him. But he did not. He unclipped himself, clipped in the Yard, waved off the Huey, and turned to face the forest. He shot six NVA point blank before being gunned down by the swarm of hundreds of enemy fighters.

They sent the last air strike directly on his position.

Invincible.

A Way, not The Way—Whether Epictetus would agree with this interpretation of his ideas or not, I do not believe this can be argued: the Old Man would have us be killable, yes; but breakable—never.

Undismayed, and yet devoutly offensive for the good of the whole.

What then? is a passion project.

If you believe more people would profit from these ideas, please consider becoming a paid subscriber, leaving your thoughts below, and sharing this essay.

I also wrote about a Vietnamese helicopter pilot for SOG, a SOG operator who had his enemy surrounded “from the inside,” SOG who literally dropped bombs on his own position, and how stalking is the cure boredom.

“My hunch is he uses such extremes so that if his students take in merely two percent of his teaching, they will be better humans.”

I’m reminded of an interview with a dog trainer I once read, who was being asked why his methods were so harsh. He replied that his clients only enacted about 10% of what he recommended, so he dialed things up tenfold to make sure what needed to get through, did.

Great stuff as always, Sam.

...killable, yes; but breakable—never. This should be taught from the early days of any human being. It should be an instinct built in all of us. Maybe it is, and we just forgot it.

"What ought one to say then as each hardship comes? I was practicing for this, I was training for this." Just be mentally and physically ready. You can't separate them.