What WWII Can Teach Us About Loving Fate

Or the curse of the Expectation Society

“Yet man is born unto trouble, as the sparks fly upward.”—Job 5:7

The gulf between society’s expectations of ease and nature’s reality of suffering staggers the mind.

My sense is we live in an Expectation Society. There is a growing belief that our fate ought to be loved; that every aspect of life should be loveable.

I believe the roots of this idea stretch back to Nietzsche: “My formula for greatness in a human being is amor fati: that one wants nothing to be different, not forward, not backward, not in all eternity. Not merely bear what is necessary, still less conceal it… but love it.”1

This sounds like a beautiful philosophy. It sounds bold and hits like a double shot of espresso. It has the brain-sparking power of Nietzsche’s prose that stick like a dagger in the mind, but which, when we place it in our hands, vanishes and leaves us wondering what he actually meant. The crucial point is the power of Nietzsche’s aphorisms lies in their ambiguity, and it is in this ambiguity we find conflicting interpretations. And so the aphorism becomes a mirror of the reader, the culture, and the era.

My hunch is Nietzsche meant this poetically but that many at present take it literally. I am not referring to those who accept fate, but those who actually expect to love it. What a burden. What an expectation. I am convinced this sets them up for a life of misery.

What, then, will they miss out on when it comes to the human experience?

Let us join an infantry officer in WWII to flesh out what loving fate demands of us.

George Wilson tried to sleep after an assault when he was woken to discover hundreds of Nazi soldiers on the hill he and his men would have to climb the next day. He called in an artillery strike and it was denied. An officer in another unit looked at his map and said his men were already on the hill in their fox holes. Wilson sent a small patrol to within fifty yards of the hilltop and they found Nazis with trench coats, stahlhelm helmets, uttering guttural jas and neins. Denied artillery one last time, Wilson was furious.

The next morning, the commanders in the rear assured Wilson it would be fine, and he was ordered to march up the hill to join the armored officer and his men. When he walked a mere three hundred yards across the field at the foot of the fatal hill, “the sky fell in, and we were in hell.” Artillery rounds, mortar shells, machine guns, and tank-mounted 88s churned the earth with invisible teeth. Tanks blasted Wilson and his men with cannon, and then the machine-guns riddled the crouching soldiers. Arms and legs soared skywards amidst plumes of black and red soil. Minds grappled with control: “I had to fight with all I had to keep from going to pieces. I had seen others go, and I knew that I was on the black edges. I could barely maintain the minimal control I had after 14 or 15 days of brutally inhuman fighting in those damned woods; I had reached the limit of my physical and emotional endurance.”2

What then? Where is the love?

When men with meaty exit wounds scream for medics to no avail because the Nazis killed every corpsman with a crimson cross on his uniform—where is the love? When cousins of chimpanzees march against steel plated Panzer tanks and the point man goes insane beneath the bone-rattling barrage—where is the love? When a calm and masterful sergeant walks like Ares across the field of war only to be shot in the temple by a German sniper—where is the love? And when 100 out the 150 by our side on that day are shot, shredded, delimbed, and killed, and when all of this happened because one arrogant rear echelon officer of slightly higher rank could not read a map and would not second guess himself—where, then, is the love?

No. There can be no strong affection for fate. No warm attachment. No endearment as if we love bits of bone and flesh flying about in the air and glimmering under the sun in the mud. And thus one moment of reality renders a “luxury belief” obsolete.

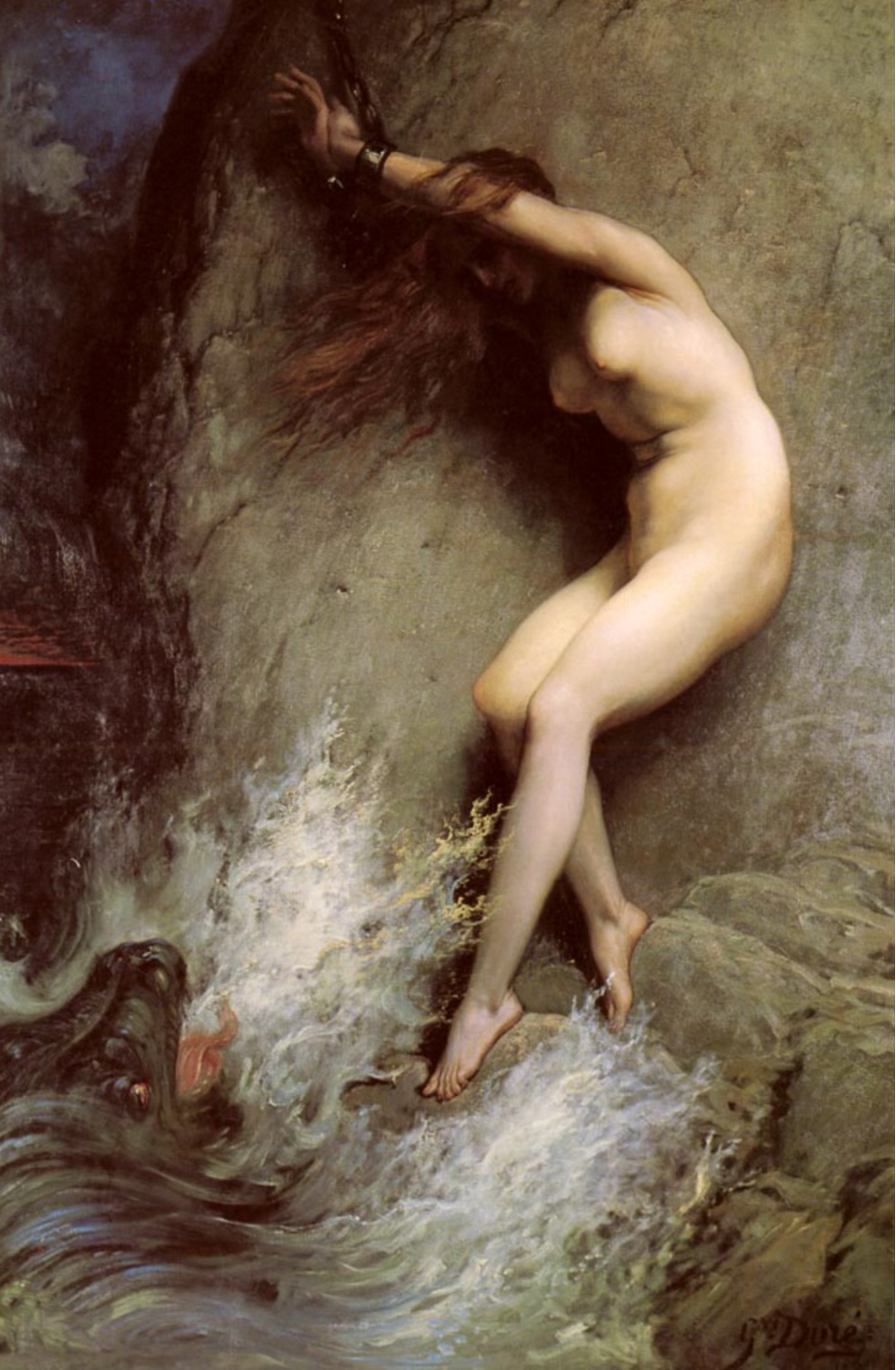

But what says Fate? Alas, she is silent. She does not speak—she simply is. She is not merely an unpleasant job or a power outage in a storm. She is the trip wire beneath the yellow leaves. She is the ridge crowned with tanks. She is death. What other animal can love fate? Can we imagine a zebra loving its fate when its meat is gnawed off its bones by a lion? Or a lion loving its fate in a cage when its dignity is gnawed out of its soul by humans? Only the human animal can fool itself into loving fate, and this can only happen in a novel environment—ease. It is an irony that this delusion is only possible due to the sacrifice of those who knew fate could never be loved.

The Expectation Society, then, reveals its affluence, its safety, and its fragility. It does not know that on the other side of ease existence-as-we-expect-it-to-be is subordinate to existence-as-it-is. The primary delusion of the Expectation Society is thinking not only we should love fate, but that we can.

I see three ways to respond to suffering when expectations of a lovely fate shatter on the shores of reality. The first is to glide into a black pit of denial when reality is too much to bear—evasion. The second is to burn the world and everyone in it to ashes in anger that expectations were broken—nihilism. And the third is to find enlightenment in suffering and plant our knuckles in the black soil at our feet—ownership.

Only by accepting the truth of suffering can we begin to master it.

We may now lean into a reading of Nietzsche’s words more attuned to his actual meaning. His body—and later, his mind—were breaking. I do not believe he loved his fate: migraines, vomiting, gut pain, the creepings of insanity. I believe he, and Wilson, and all those who suffered greatly, loved not fate but their ability to suffer their fate—and to suffer it beautifully.

So it seems fate does not reveal what we will become so much as it reveals what we choose to make of ourselves.

What, then, do those in the Expectation Society miss out on?

The opportunity to make their response to suffering the meaning of life itself.

What then? is a passion project.

To support my mission, please share this essay, leave a comment, or simply add a like.

See you for the next essay on Tuesday.

Nietzsche, Friedrich. Ecce Homo. Translated and edited by Walter Kaufmann, Vintage Books, 1967.

Wilson, George. If You Survive: From Normandy to the Battle of the Bulge to the End of World War II. Ballantine Books, 1987.

“Suffer beautifully.” Incredible piece as always brother.

I often reframe the word love to acceptance. There’s obviously a semantic difference between the two emotionally, rationally, however, I’m not sure there is.

Complete acceptance of a person or circumstance is rational, unconditional love that can allow focus to remain on what we can control. Still playing with the idea but that reframe helps me with the concept of amor fati in response to life’s most difficult trials.

Appreciate you 👊🏻

“The second is to burn the world and everyone in it to ashes in anger that expectations were broken—nihilism.”

This is the option most revealed in today’s culture.

Good one Sam. The world keeps coming (fate) and we can only choose how to respond.