The Cause of Stress Is Self-care. The Cure for Stress Is a Good Fight.

Monty Python, Dugum Dani, and a pale blue dot

I have had some incredible conversations with my readers. Some have sent me life-changing books, others have supported the existence of What then? with generosity I never would have imagined, and still others have left comments that still have me thinking.

When I started What then? with zero footprint as a playground for ideas, I imagined my essays would vanish in a void. Thank you for being here, genuinely.

Let’s get after it.

My experience is that the stress of modern safety ends only when shared danger begins. It does this by forcing us out of self-obsession and into a common fight.

I was reading the Wall Street Journal when I came across a short essay by a stress physiologist. She wrote about a stressful event she recently went through. When she flew to Hawaii to give a keynote speech and her luggage was lost, she was, ironically, stressed about it. But then a lady at a random store suddenly gave her the keys to her brand new BMW to go shopping for an outfit. The lady said “Just bring it back when you’re done.” The physiologist was stunned. She wondered how this act of kindness was possible. Her stress was no longer such a burden.

Her point was simple and clear: service is a path to relieve stress, both for those who do the serving and those who are served.

But when I read her story, I had to laugh. I was struck by the reminder that the inverse is also true: oppression can cure stress as effectively service.

We can find examples of this truth in nearly any combat memoir or study of pre-state peoples. I pulled The Dugum Dani off my shelf, flipped to a dog-eared page, and behold: Heider, the ethnographer living among these feisty New Guineans, witnessed their bow and arrow battles and midnight stalks, and documented their 28.5% violent mortality rate for males.

Heider had this to say: “In the face of war, death, and ritual,” where those who are used to safety would expect to find stress, “the Dani seem calm and relaxed.”1 In an amusing observation, Heider writes that in the middle of a battle “…personal names and personal joking insults are thrown back and forth along with the arrows.”

Sure enough, an enemy oppressor can be as effective a stress reliever as a random lady offering us her BMW. How so? Oppressors motivate us to put our back against the wall and put a spear in our grip. To build a tribe we are willing to fight and bleed for, one whose lives are more important to us than our own. In a sense, an oppressor recognizes us. I love having an enemy who is honest enough to make himself known. Our relationship becomes clear. Our inner energies that otherwise might turn against us in the form of self-sabotage may now be channeled outwards into a productive task, such as keeping our loved ones alive until sunrise. This can even be seen in the physiques of the elderly Dani: they had to be useful, and were thus graced with youthful limbs of twisted steel and a lethal spryness in their stalk.

So in a way, the risk of being killed can be less stressful than losing a bit of luggage, depending on our perspective.

Still, this seems strange.

It reveals the more fascinating question is not the cure for stress, but the cause.

My hunch is that the most significant cause of stress at present is this: the deadly duo of indifference towards others and obsession with ourselves. An obsession with how we “feel”. With how we think our lives “should be.” And it follows we are stressed when others are utterly indifferent towards us. Two humans locked inside of their own skulls as they pass each other in the street, neither loving nor hating nor deeply evaluating the other—this is no good for an animal evolved to come alive when its life is threatened. The enemy no longer stalks through the night with a spear—it is now the living-deadness permeating our safe and modern world.

It is clear that safety is a gift, and yet a gift many use to knee-cap themselves. Without danger, why serve an ally or be served by one? Without danger, why oppress an enemy or be oppressed by one?

And what then? What happens when the world of danger cannot punish self-obsession? The result is rarely ever good. Let us take it to the extreme with a little poetic license and play with a few different expressions of self-obsession.

If the self-obsessors withdraw into a cocoon of their own wretchedness, perhaps the world will wither away as the population drops to zero. If they evade the responsibility of owning their individual existence, perhaps they will kick off yet another Borg-like mass movement to abolish the “self” altogether—Nazism, Bolshevism, Maoism, Transhumanism, the list is woefully long. If they decide to destroy the world instead of themselves, perhaps they will turn it into Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, and then at last their inner hell may not look so bad in comparison to their outer hell. Finally, what if they decide to bear their needless self-victimization like a cross? Perhaps they will bring on an age of self-immolation like the flagellants of the Black Death, who deemed it wise to whip themselves with leather thongs of knotted cords with bits of metal on the tips (or in a different version, with wooden planks).

What then is the solution to avoid such foolish and yet possible fates? We already know it. It is not to join the ranks of the indifferent and self-obsessed. It is to give a damn about each other as if a momentous new age were beginning, for in fact it is. It is to treat each other as if we were sharpening our spears for a good fight against a savage enemy screaming down at us from the hills

The woman who lent the stress physiologist her car revealed why she did this seemingly charitable act: her daughter moved to the mainland, and she hoped “somebody might do something similar for her if she was in the same circumstance.”

This is what evolutionary psychologists would call reciprocal altruism: we are likely to bestow benefits upon others “as long as the delivery of benefits is returned or reciprocated at some point in the future.”2 It is for me to give you a banana in the hope you will give me impala meat when I have bad luck on the hunt. It is for you to fly into my firefight to save me right now so that I will fly into yours and save you tomorrow. This is why we are here today and our species did slip into extinction via self-care.

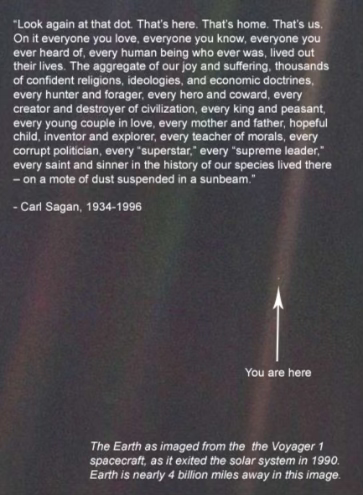

And this future return need not be to us, but to those we love. It is to pick up the elderly lady’s shopping list when she drops it at the grocery store because we want the universe to pay it forward on our “pale blue dot” drifting in the cosmos. The world is no longer made of tiny bands of Dani who can massacre each other without anyone noticing. It is now a global community: our fates are aligned.

Thus the cure is to do both. It is to serve others as an ideal, as allies. And it is to prepare for oppression as a reality, against the enemy in the hills.

This, too, is a cure for stress.

If you enjoyed this, please consider adding a like and restacking this essay.

Heider, Karl G. The Dugum Dani: A Papuan Culture in the Highlands of West New Guinea. The Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research, 1970. I used this excellent ethnography for all quotes and info on the Dani.

Buss, David M. Evolutionary Psychology: The New Science of the Mind. 6th ed., Routledge, 2019.

A good piece and well said. Having played around with the psychological drives for right action, My current assessment is that reciprocity expectations are a cancer that undermines my efforts, a scorekeeping that leads to frustration and less good done for the world. Though kindness does beget kindness sometimes, I am not friendly so that I will be befriended, nor do I help so that I might be helped, nice as all that would be.

Instead, I focus on being the person who does what's right because that's who I am and what I want to create in the world. Though I'm aware of and comforted by the large body of psychological research showing disinterested good actions change us and lead to what might loosely be called eudaimonia. So the unreciprocating receiver of a good deed is shooting themselves in the foot as effectively as if they choose Cheetos over chickpeas or the couch over exercise when they do not find a way to pass on the good. The only real question is if I want to shoot myself in the foot too by holding back.

“My hunch is that the most significant cause of stress at present is this: the deadly duo of indifference towards others and obsession with ourselves.”

You got that exactly right, Sam! Reminds me of these wise words from Joseph Campbell:

“When we quit thinking primarily about ourselves and our own self-preservation, we undergo a truly heroic transformation of consciousness.”