The Cure for Meaninglessness Is a Task

Shackleton and pursuing excellence

This essay edges up against one of the core themes that forms the basis of the book I’m writing. I call the idea “primal hardship.” I have its conceptual framework mapped in its entirety, and this piece plays with it a bit.

I like the essay format precisely for this reason—it is play. What else are essays for if not to experiment, riff, temporarily suspend nuance, speculate on risky ideas, and risk looking like a fool in order to discover an idea that might be life-changing?

It is how I found the idea in the first place.

So, let’s get to this essay and speculate a bit.

We hear these phrases more and more often: “My job is pointless. My calendar runs my life. Our food is poisoned.” And then it swells: “Democracy is under attack. The system is rigged against me. The earth is dying. Humanity is a cancer.” And it is not unimaginable a few specific questions lurk beneath them: “Why do I live? Why was I put here? What should I live by?”

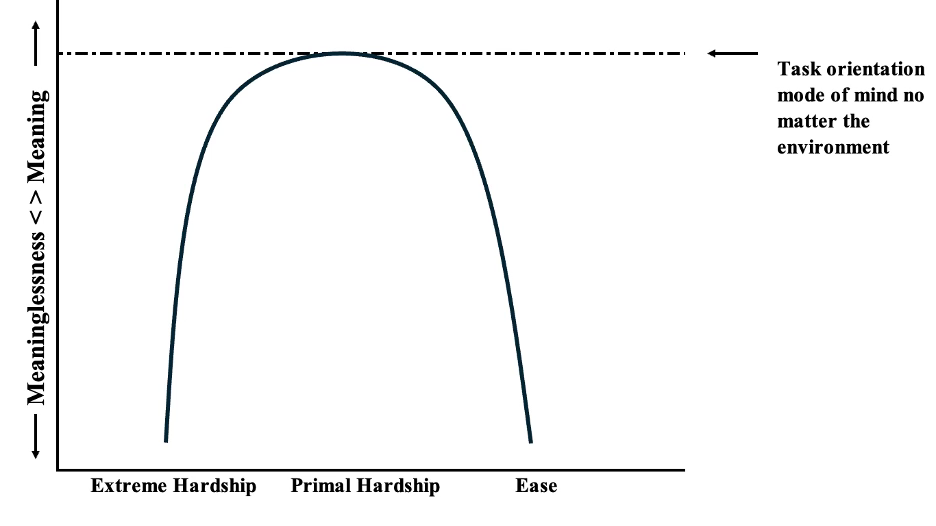

This is a malady I have written about in prior essays. This is a crisis of meaninglessness despite our era being the safest and most privileged in human history—despite ease. But writing about this crisis in ease with its abstract threats has come at the cost of ignoring meaninglessness found at the opposite end of the spectrum: in extreme hardship.

Why does this shift in focus matter?

Because my hunch is the cure for meaninglessness in ease is the same as the cure for meaninglessness found in extreme forms hardship. Sir Ernest Shackleton described the perfect example of this truth. His memoir, South, is a gold mine of experiential wisdom that yields more fruit than any mass-market self-help book ever could because his lessons are written in blood.1

One story hooked in my mind.

Shackleton and his men crouched in their tents on an arctic island with wind so wicked it would knock the skeletal survivors off their feet. Their ship sank in the arctic, and they were well over a year into their brutal survival and near starvation. One man “had expressed a desire to lie down and die.”2 Shackleton immediately grabbed the man with the suicidal soul and set him a task: keep the little stove fire alight. Shackleton wrote the results: “… it took his thoughts away from the chances of immediate dissolution. In fact, I found him a little later gravely concerned over the drying of a naturally not over-clean pair of socks… occupation had brought his thoughts back into the ordinary cares of life.”

This is satisfying. I love that a man can endure death-by-isolation, death-by-whale, death-by-ice, death-by-starvation, and an ironic death-by-dehydration while surrounded by gorgeous fresh water icebergs, solely by focusing on drying a pair of socks. Shackleton’s wisdom is the sort of wisdom the mind begs us to remember in case we ever find ourselves in a leadership position while stranded on an island or in a concrete bunker during a nuclear holocaust.

Then I wondered why meaninglessness arises in extreme hardship in the first place.

Well, why would it not? Killer whales might smash through three feet of ice beneath your feet and drag you down into black water and eat you with weirdly thimble-like teeth. Ice floes might ruin your ship and trap you on an arctic island. A colossal shard of iceberg might slide into the sea and send a thirty foot tidal wave of freezing water at your paltry tent pitched on a few pebbles at the foot of a cliff. You might starve. Get frost bite. A man can die and not even know it. It is a never ending game of drop-the-soap.

My point is thousands of mortal tasks must be taken into account at all times. So meaninglessness in extreme hardship arises from too many existentially significant tasks, and this draws our attention to the million horrors outside of our control. Now returning to ease, my sense is meaninglessness arises from a lack of existentially significant tasks which, ironically, also draws our attention to the million horrors outside of our control.

It seems, then, in both extreme hardship and ease we may be blinded by the million horrors outside our control and not the only thing that will ever be under our control: choosing a task of consequence.

The cure to meaninglessness is this: absolute excellence consciously applied to a single existentially significant task. Mind, body, and soul dialed in and cranked up to the maximum, for one task.

This makes sense, and it glides into my larger project within the What then? universe. There is a specific amount of hardship I have been honing in on in which meaninglessness cannot get out of hand. “Primal hardship” is neither too much hardship nor too little. I call it primal because it was the rule throughout evolutionary history.

The crucial point is that it is possible to be primal today, for it is in fact a mode of mind. What this mode of mind is, why it exists, what destroys it, how we can get it back, and how to improve upon it in the modern world is the foundation of my book.

But for now, what do those with primal minds do?

They set themselves a task.

Take running: do trail runners say “this is such a worthless thing to be doing” while dialed in to every root and branch and creek on a run, or are they high while focusing on the rhythm of lungs, legs, and leaves?3 Take labor: do those in the middle of a muscular task doomscroll X or Insta or Meta to bury the void within with bullshit, or do they stand in awe of some green and growing thing with a shovel in their hands? Take hunting: do hunters moan “woe is me” while stalking a stag in a dell, or are their minds merged with footholds and winds and silhouettes? Take close quarters combat: do operators flowing room-to-room hunting a terrorist holding a pistol to a hostage’s head cry out to the gods to give them a reason to live, or is each second rich with meaning?

How could they? In primal hardship, each moment is existentially significant and vibrantly alive, whether we are drying a wretched sock or ridding a room of insurgents. Each moment is consciously reduced to a task of consequence.

The Merriam-Webster dictionary is wrong. Its definition of meaninglessness paves the way for self-victimization. Meaninglessness is not passively “lacking any significance” as if this were a condition outside our control like E. coli or grey hair. Meaninglessness is nothing more than choosing to focus on what is not under our control as opposed to what is under our control.

What then can we say to the voices of meaninglessness, both those around us, and most importantly, those within us?

For my part, it makes for an epic ode: Can you not break your dependence on the world around you with a mode of mind that transcends your circumstances? Can you not turn the present moment into a noble task, even if the only thing left is to die well on a desolate rock in the arctic, or to find a bit of serenity despite the apocalyptic fools on the news? And can you not complete this task—clearing a room, walking a mutt, reading a fable to a child, drying a pair of socks—with the purest excellence you are physically and mentally capable of?

If you enjoyed this, please consider adding a like, restacking, and sharing this essay.

This is how more readers find my work.

Shackleton, Ernest. South: The Endurance Expedition. Penguin Classics, 2017.

Check out this great piece by Jesse C. McEntee on trail running.

Again and again the great commanders taking over a new army impose new high standards of discipline, cleanliness, hygiene, fortifications, regular drills, immaculate weapons cleaning, and the same is true for sailors on board ship, when there is not a lot for high energy young men to do.

William Blake writes about seeing the universe in a grain of sand, and meaning can be found in meticulous self-discipline and attention to detail and the self-confidence they generate, the knowledge you’re ready for action, whenever the opportunity may come.

Have you read any of Plutarch’s Lives? You’d find the great commanders worthwhile: Lysander, Sulla, Sertorious.

“Primal Hardship” and “task” clarifies something similar that I see. We have been convinced that ease and happiness are the goals in life. However, I think hardship, pain, suffering, and the overcoming of limitations is the real state in life. Think about the success of a professional sports team. If their singular goal is to win a championship, then they will probably fail. If their goal is maximized their capacity to overcome their limitations of time, talent, background, and relationships, they create a dynasty and have a hall of fame career. In effect, trust the work, not the outcome.