Why Chivalry Will Never Die

From J.R.R. Tolkien, to C.S. Lewis, to hunter-gatherers

I have read the Lord of the Rings nearly every year since I was fourteen. One scene that is forever hooked in my mind is one of the most subtle. It almost comes across as an aside, a minor musing that Tolkien added in an absent minded riff.

When the Dúnedain—a race of noble men in Middle Earth—found Aragorn and the remaining fellowship outside Helms Deep, Gimli, looking at these stoic warriors from afar, observed “They are a strange company, these newcomers,’ said Gimli. “Stout men and lordly they are, and the Riders of Rohan look almost as boys beside them; for they are grim men of face, worn like weathered rocks for the most part, even as Aragorn himself; and they are silent.” Legolas then adds the kicker, “But even as Aragorn they are courteous, if they break their silence.”1

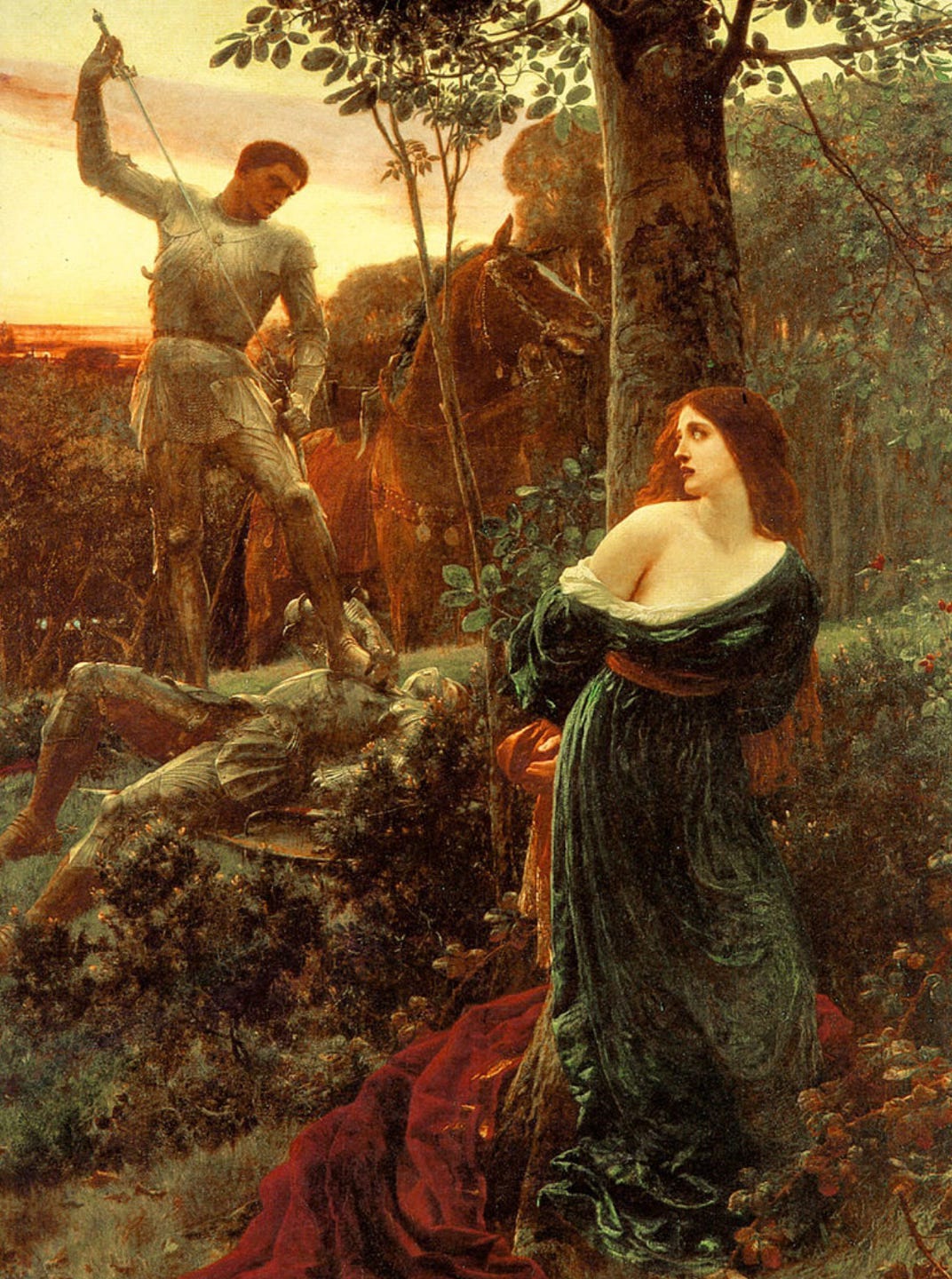

Tolkien is talking about chivalry. What was once an ideal to strive for—though rarely ever attained—is now mocked as sexist, or secretly yearned for, or lamented as unrealistic.

Why does chivalry matter? Let us do a thought experiment. What if Aragorn were hunched and sneering, and, when speaking, both rude and mocking? He would be an Orc—a monster. What if he were weak yet mannered? He would be Wormtongue—a rat. And what if he were lordly yet cruel? He would be Denethor—and ass. The chivalrous are unique in that they take upon themselves a dual burden—strength and silence, power and courtesy, violence and restraint. So why does chivalry matter? Because without it, then, all we may be left with are varying degrees of monsters, rats, and asses.

My feeling is that those who have read the Lord of the Rings one too many times feel a gravitational pull towards this chivalrous mode of life.

Can it be a lack of chivalry on earth that draws us into the chivalry of Middle Earth? This question leads me to an even deeper question: can chivalry die?

C.S. Lewis wrote a brilliant essay called The Necessity of Chivalry. In it, he argues that the man who is truly chivalrous “is a work not of nature, but of art.” In other words, the chivalrous combination of both “stern” and “meek” is unnatural. Chivalry, then, can die.

To prove his point, Lewis writes about those who are unchivalrous, starting with bullies in school. He goes on to write that before bullies there were WWI veterans who fought like madmen in war but who in peace could not turn off the madness; and further back in history, there was Atilla; and further back, the Romans; and even further back, the olive-oil-lathered Achilles. But if we are talking about human nature, why stop at 3,000 years ago on the beaches of Troy? Why not go back 20,000 years ago and witness our ancestors in nature?

Let us look at the Aché, a true hunter-gatherer band, and hold them up as representatives of our forebears.

An Aché man would sit alone near a fire in the forest beneath a pale moon. The ancient creed of an Aché man speaks volumes: “I am a great hunter; I kill much with my arrows; I am a strong nature.”2 But this lordliness and lethality carried weighty demands.

Just as medieval knights treated their own with grave courtesy only to view the enemy as hostile, so too did the Aché. When it came to the enemy, they must be able to activate what I think of as a primal-recall and, in an instant, exercise extraordinary violence against their enemies: “There is only one language that can be spoken with them, and that is the language of violence.”3

But this capacity for extraordinary violence is not meant to face inward. The Aché must make a clear distinction between violence and power within the band. To prove himself, a man must not “exercise his authority through coercion, but through what was most opposed to violence—the realm of discourse, the word.” Why must he put aside bow and blade for discourse? It seems that if a man is both violent and incapable of discourse, he will be left alone in the forest to die. Simple. When a few million men and women—fewer than the current population of Manhattan—walked the entire planet, and there were vast plains, mountains, deserts, islands, and hills to roam, there was no patience for arrogant peacocks.

This dance between violence and discourse is ancient. It is human.

Our ancestors—those “naked and savage poets”—lived on a barbell. They maxed out the margins of human experience. They had to. On one extreme, they were lordly, grim, strong, stern, weathered, and violent, and on the other extreme, they were courteous, humble, selfless, meek, restrained, and expendable. Nature did not give a carrot to those who were neither lordly nor courteous—she gave them a stick and a dirt nap.

I believe the great C.S. Lewis was wrong on this point.

I believe in my bones that chivalry is to our hearts what oxygen is to our lungs and reason to our minds. We do not need to lament the nature of mankind—we need to live up to it.

What then? If chivalry cannot die, then where is it?

In the ancient world we had to be lordly amid spears and savages and courteous amid kith and kin or else we would be dead. In the modern world, we are witness to something novel: the deadly duo of ease and technology, which then leads to the fatal flaw of our time—a lack of repercussions for word and deed.

When it comes to ease, we are rarely ever called on to be chivalrous by Natural Law or a Code. We suffer neither expulsion from the band nor attack by the enemy. And when it comes to technology, I cannot picture the Dúnedain on a podcast talking about how epic they are, how many Orcs they slaughtered, and how weak all other men are what with their pink and uncalloused hands. So we neither need nor see chivalry on a daily basis.

And in this evolutionarily unimaginable world of chatbots, texts, emails, posts, blogs, and comment sections, of nanny states, of lawsuits, of safetyism, of paternalism, of look-at-me social media, the unchivalrous flourish, sitting on their thrones of pixels, and then hiding, taunting, trolling, bragging, bullying, cursing, threatening, and basically being Orcs without fear of reprisal. Alas, the duel is now illegal, and we can no longer challenge one of these Techno-Orcs to six-shooters at dawn.

My point is that chivalry is now a choice. How, then, do we bring it back?

If ease and technology are not built for the chivalrous—those who “speak softly and carry a big stick”—then we must find it elsewhere. My sense is that we need to believe in it again. Why not learn from the silent Dúnedain, the elegant Elf, the wise Wizard, the hungry, short, sensible, and surprisingly sturdy Hobbits of the Lord of the Rings? Or the laughing, witty, singing, rowdy, jousting, happily fatalistic knights of Ivanhoe?

The novel has preserved the chivalry in our blood.

From ink on paper, maybe chivalry will spread, and bit by bit, we will see traces of it in subways, stores, and streets, and then in the techno-world, and then what began in the forests of our species youth will once again be the Law.

What then? is a passion project.

To support my mission, please share this essay with a friend, share your thoughts below, or simply add a like.

See you for the next essay on Tuesday.

Tolkien, J. R. R. The Lord of the Rings. HarperCollins, 1991.

Clastres, Pierre, et al. Society Against the State: Essays in Political Anthropology. Zone Books, 1987.

Clastres, Pierre. Chronicle of the Guayaki Indians /. Zone Books, 1998. I also use this for the rest of the quotes relevant to the Aché.

I’m not a fan of Tolkien. There, I said it. But I think LOTR and other renditions that reflect complex societal landscapes reflect two, rather than one, societal “couplers”: *Chivalry* and *Fama.*

The chivalric code was a moral ideal, social construct and behavioral framework that defined aristocratic conduct. It blended faith, martial prowess, and courtly etiquette into the defining algorithm for personhood.

*Fama* refers to the medieval conceptualization of reputation or public standing, in particular, how individuals were perceived within their communities — it encompassed honor, gossip, and the social dynamics that influenced how a person’s character and actions were discussed and interpreted by others.

If you want a sense of how important “fama” was, and its interplay with chivalry, the Tuscan poet Guittone d’Arezzo wrote “for shame is more to be feared than death, / … for a wise man ought to sincerely love / a beautiful death more than life, / for each person should believe that he was created / not to stay, but to pass through with honor”. One observer noted that all members of Florentine social hierarchy subscribed to the sentiment that “a man who does not look to his fama is insane, and though living, might as well be dead.” When you consider that the “males of aristocratic families were trained to do violence, routinely carried arms, and were prickly about their honor,” you can see why “bona fama” (good reputation) and “mala fama” (bad reputation) were deadly serious business.

The chivalric code and “fama” — honor and reputation as both a connective tissue and a currency — were best exemplified by wisdom, reason, loyalty, moral integrity, courage, virtue, and purity. Of course chivalry also had its dark side and abuses — pride, violence, and moral corruption.

Two excellent books for reference:

Chivalry and Violence in Medieval Europe

Fama: The Politics of Talk and Reputation in Medieval Europe

Your excellent essay triggers so many thoughts and ideas for me that I just can't condense them into a comment. Take that as a compliment on the richness of your writing and questioning Sam. The question of how "we" can call out the better angels of our nature, rather than pandering to our baser instincts, might be the main existential challenge we now face as a species.