A Rendezvous With Death Reveals The Value Of Life

A riff on Alan Seegers war poem

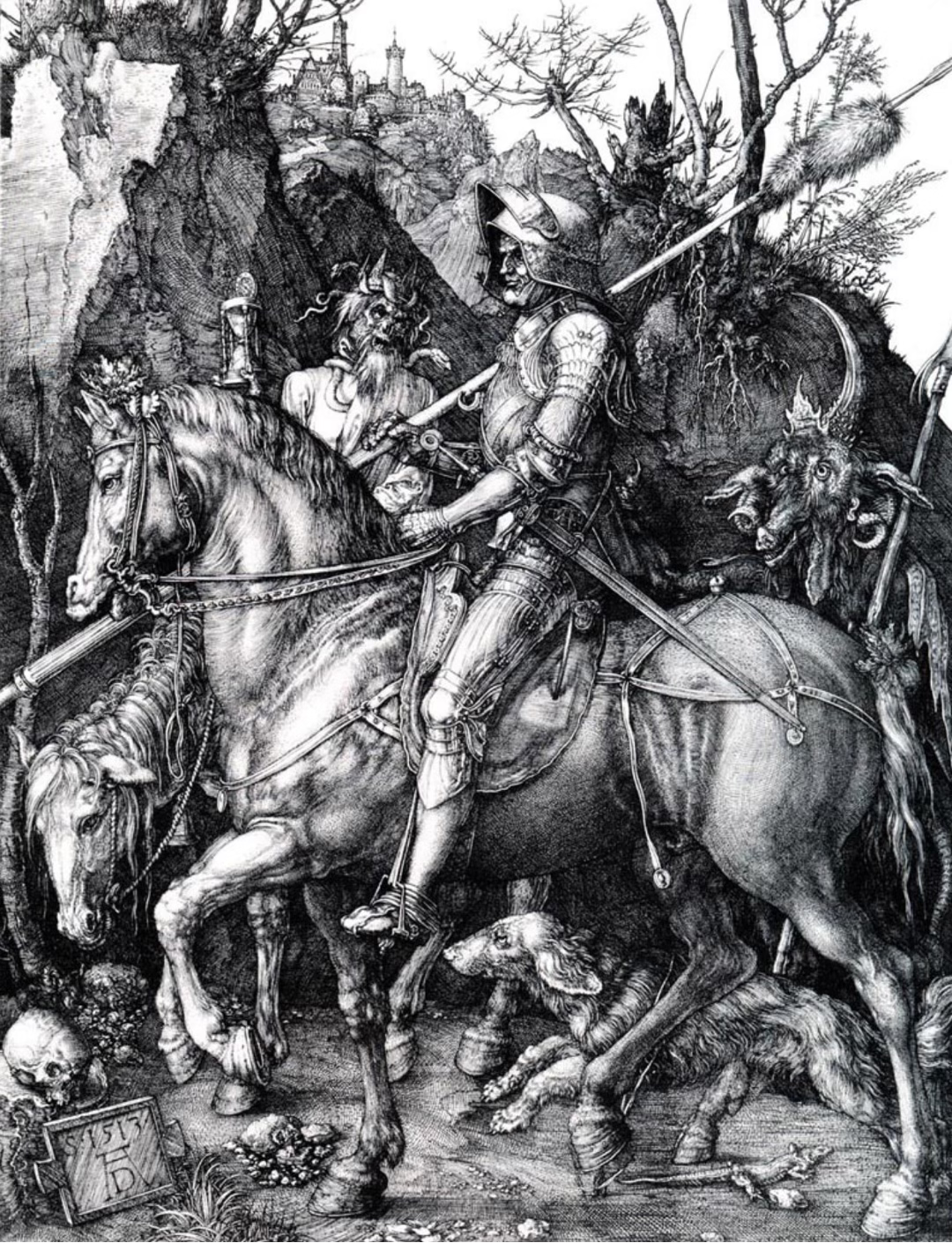

Civilization is on a crusade to atrophy both mind and muscle. I believe there should be a counter crusade to harden them.

Alan Seeger was a war-poet. America had not yet joined WWI, so Alan volunteered for the French Foreign Legion and a life in the violent vineyards of France because, he said, he cared for only two things in life: truth and beauty.

While convalescing in a hospital prior to returning to the smells of cordite and corpses, he wrote twenty-four lines1:

I have a rendezvous with Death

At some disputed barricade,

When Spring comes back with rustling shade

And apple-blossoms fill the air—

I have a rendezvous with Death

When Spring brings back blue days and fair.

It may be he shall take my hand

And lead me into his dark land

And close my eyes and quench my breath—

It may be I shall pass him still.

I have a rendezvous with Death

On some scarred slope of battered hill,

When Spring comes round again this year

And the first meadow-flowers appear.

God knows 'twere better to be deep

Pillowed in silk and scented down,

Where Love throbs out in blissful sleep,

Pulse nigh to pulse, and breath to breath,

Where hushed awakenings are dear ...

But I've a rendezvous with Death

At midnight in some flaming town,

When Spring trips north again this year,

And I to my pledged word am true,

I shall not fail that rendezvous.

He returned to the front a few months later for the Battle of the Somme. Staged in a cornfield for the charge, he stuffed bits of scrap paper scribbled with poetry in his pocket, fixed his bayonet, and smiled at his friend. When he rose to sprint across no-mans-land, he took several bullets from a German machine gun.

He did not fail his rendezvous.

What then?

This poem puts words to something elemental in us all. I believe it says No. It is a rebellion. But a rebellion against what? And if it is against something, then it must also be for something. So what is it for? My sense is that this poem reveals a split in the human condition that came about with the creation of civilization. Let us call the two halves born from this breach the main-life and the margin-life.

Main-life: It looks like apple-blossoms, blue days, a house, a desk, a steady job, safety, stability, routine, wealth, possessions. It is made of pleasant things. But rarely does it test our conviction or force our focus on some dire moment in time. It does not want us to see the rendezvous. It delays it, blurs it, and opens us up to the fate of Tolstoy’s Ivan Ilyich who slipped into an existential horror when he realized he had never really lived as he was about to die; he thought the pleasantness of life would last forever. “It occurred to him that those barely noticeable impulses he had felt to fight against what highly placed people considered good, barely noticeable impulses which he had immediately driven away — that they might have been the real thing, and all the rest might have been not right.”2 It seems, then, that the main seeks truth and beauty, but falls short. Why? And how? We will come back to it.

Margin-life: It is what most people do not want to think about. It looks like mud, pain, ice, a 70# pack of bullets and grenades and rolls of gauze, cancer, a glinting bayonet, broken bones, the taste of copper, the blood-drunk screams of the enemy across barbed wire in the black of night, and the risk of an ultra-clear death. But these same traits make the margin a place where each hue of blue and breath of air and sigh of leaf and sip of wine can be worshipped as each second of life becomes more valuable. It is a “pledged word” backed by blood. It is a conscious choice to die for a thing worth more than life itself. It is here, of all places, that we find truth and beauty in the raw. Stripped of all excess. Pure.

Truth and beauty are not synonymous with pleasure.

For my part, the savage thrill I get from this poem is from its No to the false promise of the main-life, and its Yes to the ascetic beauty of the margin-life.

Still, this seems strange. Why would those who want to know truth and beauty feel compelled to walk away from warm skin and soft breath upon a bed of down bedside them and choose the risk of death? Why do they trade “scents of down” for the scents of war — oil, dirt, cordite, steel, sweat, blood? And why do they not rest on velvety pillows and send some anonymous schmuck to die in a trench in their place?

Let us do a thought experiment. Let us look at a society privileged enough to have a main in the first place, a society like ours. If those who embody the margin — either in 1916 or 2025 — say No to war-cries and mustard gas and Yes to milk-white sheets and fire-lit cafes, the main would vanish in a fiery inferno in a matter of days. Maybe minutes. Yet if all those who live in the main said Yes to the margin and leaned into those savage screams and felt those tiny hairs on their neck and arms lift in anticipation of a night of adrenaline beneath the moon, the margin would still be there at sunrise — and so would the sheets and cafes. It seems then that the truth and beauty of the main can only exist as a result of the risk of death on the margin.

The margin was once all there was. The main is an evolutionary curveball built with noble intentions: to escape the miseries of the margin. But misery cannot be escaped from because our baseline for misery merely shifts. Is it any surprise that people can despise all that is good and golden about the main-life until they know what it is to crouch in a coal mine, or crawl through trenches, or walk through a favela?

The crucial point is that the main-life becomes lies and ugliness for so many without a taste of the margin. We are animals of extremes. Our war-poet understood this when he wrote, “This experience will teach me the sweetness and worth of the common things of life. The world will be more beautiful to me in consequence.”3 So, in a sense, we only really learn the full weight of truth and beauty by learning the weight of the margin.

What then? What does any of this mean for us?

There are two main traits, I think, that define a war-poet, or those men and women who make it their mission to recon the edges of human experience: the first is a divine devotion to truth and love and peace; the other is a savage pleasure in trial and fire and oath.

We cannot make the margin easy, but we can make the main harder. It is a fitting paradox that to save — and appreciate — truth and beauty, we must be willing to walk towards our own rendezvous with arms spread wide and chins held high. How human. How ancient. How raw and primal that exploring the extreme edges of experience is the antidote to the atrophy of civilization. Why not, then, meet our rendezvous with heart and eyes open? Why not smile at doom? What feels more powerful and masterful than standing with our rendezvous in silence now and then, and owning it, and in doing so earning a full awareness of every second of life, whether we find ourselves luxuriating on silken sheets or lugging a 70# pack at midnight in some flaming town?

If you enjoyed this, please hit the like button, share it, and share your thoughts.

This is how more readers are able to find my work.

See you for the next essay on Tuesday.

Shout out to my friend Adam Karaoguz for sending me this poem. It struck me. This piece is an attempt to flesh it out.

Tolstoy, Leo, et al. The Death of Ivan Ilyich. 1st Vintage classics ed. New York, Vintage Books, 2012.

Hill, Michael. War Poet: The Life of Alan Seeger and His Rendezvous with Death. CreateSpace, 2017.

Much of life can only be understood when opposites confront one another. Life and death find their meaning in the opposite. Safety and security can only be appreciate in the experience of risk and hazard. We love our loved ones, not because of what they give to us, but what is missing if they were not here. Iain McGilchrist in his book The Matter with Things writes about this tension in chapter 20, The coincidentia oppositorum. Here's a video where he discusses this. https://youtu.be/KAZ2a-vawMk?si=LDAZbA5oW1ubnLbJ. The point here is that the Main and the Margin require the other to establish meaning and perspective. This is what I see in the Center and Periphery idea that I've written about. What happens when the Center (Main) fails and disappears? All we then have is the Periphery (Margins) becoming the Center or Main. Then quickly a new Main or Center emerges. It seems like this is where we are today. And yet, if even a time of change, we hide from the realities of death, we will fail to do that which will support and enhance life. Great thoughts for the turn of the year.

Intriguing poem Sam. I was not familiar with this poet or poem previously. It is one of those that seems simple at first glance but has a lot hidden beneath the surface. Thanks for pulling the string on this one to help us work through it. Hope you have a great year.